The Dymitruk Model

Following the methodology defined below is the most effective way to leverage the power of Distributed Version Control Systems - specifically Git. This work is the result of an in depth analysis of Continuous Intergration and the notion of responsible Continuous Delivery. The inherent risks that de facto CI and CD introduce are mitigated by what others now refer to as “The Dymitruk Model”.

Features are small

Old-school branch-per-feature meant that branches were large and long living to avoid having to integrate because it was a pain. This was a vicious circle as the feature would diverge further and further from other features or the mainline. Features should be as atomic as possible and your development process should abide by the Open Close Principle. Features should be small.

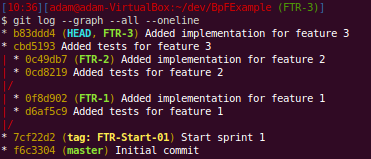

You can see that the branches have a couple of commits each. We start with the end in mind with failing tests and implement the feature in the following commit. This would be the minimal amount of commits to expect on a typical feature. They won’t typically be that small.

Integrate relentlessly

They should be integrated into an integration branch almost as often as you commit to them. This gives feedback immediately. You have some sort of CI running off of the integration branch to tell you if your changes are not adversely affecting other work. This gives you the immediate feedback of trunk-based integration while keeping your work organized and malleable.

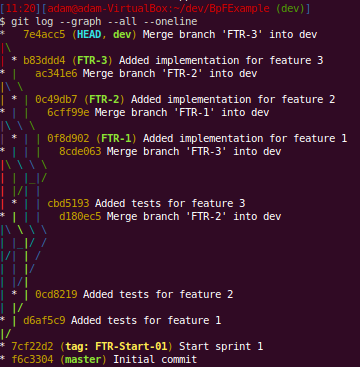

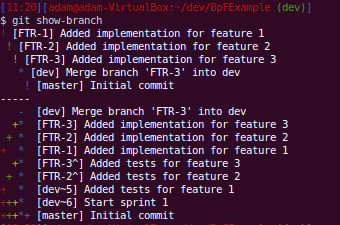

You can follow the lines here but it’s not easy as you don’t get “swim lanes” for your branches. You can see each time that we merged a feature into dev by finding the “Merge branch ‘FTR-X’ into dev”. We can use git show-branch to see what commits exist in what branches:

Just a note that we usually make the commit messages prefixed with FTR-X which corresponds to a ticket in Jira. This way you know at a glance what feature a commit belongs to.

Don’t do back-merges

Or at least avoid them. A back-merge is where you want to use something from the integration branch to help you get your work done on the feature. This is a smell that you don’t have independent stories. A reasonable middle-ground is cherry-picking. A successfully cherry-picked commit will not cause you issues when you merge in the future.

Keeping a feature branch filled with commits that only attain what the feature is supposed to do will make working with it much more flexible. An understanding of the DAG (directed acyclic graph) that makes up Git history will make this easy to understand.

Involve QA from the start

This should not even be a contentious point anymore. We all know how important tight feedback loops are. There should not be a QA department with QA employees. QA should be a hat that is worn at different or same people at different times.

Knowing what your Acceptance Criteria is and how you will prove it from the start is integral to getting a lot of things gelling - including a successful branch-per-feature regiment.

A proper DSL a la Ubiquitous Language (see Domain Driven Design) is at the heart of this. The tool that best communicates across to the Product Owner, Regression/Specification Testing and Behaviour Driven Design feedback is currently StoryTeller. One thing that it offers that no other tools offer is communication to the person writing the Acceptance Tests of what the system is capable of doing with the smallest amount of friction caused by technology. You simply pick what you want to do by clicking on links, filling out text boxes and selecting from drop-downs. There is no guessing as to how a tool might interpret your free-form text with it’s regex and English-parsing goodness. More on this in a future post.

A feature passes QA only if it has been integrated with all the other features that are completed. This brings us to a very light weight branch called QA or RC (release candidate). Once a feature is finished, it gets integrated to the RC branch and TeamCity or whatever CI tool you have makes a release build. This build upon being tested can throw this feature or any other back to development should they fail. Your CI tool/process will mark this with an incremented Release Candidate tag.

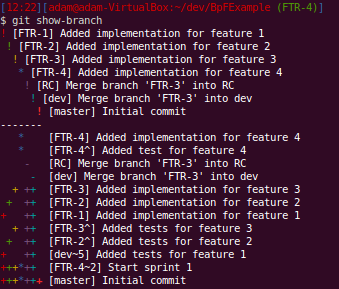

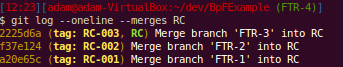

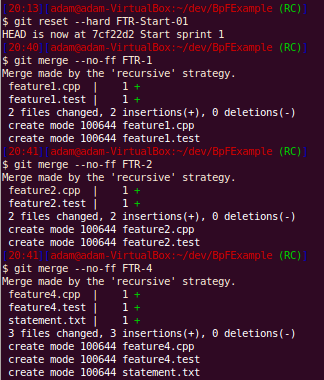

You can see that that the incomplete feature 4 is not yet part of the release candidate branch.

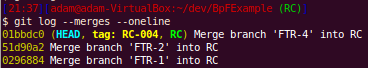

Here you can list all that’s been merged into the release candidate.

Share your hard work

There will be conflicts when you merge. This is a fact of life when work is done by more than one person. When you integrate often from your feature to the integration branch, the conflicts you solve should be remembered. This is done by git’s rerere but could be simulated in other systems with little effort. The key is to set up a way of sharing these auto-resolution conflicts to the rest of the team.

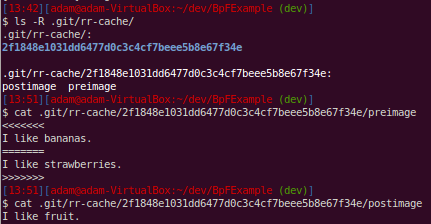

Now anyone that tries to integrate that feature and has that conflict will not have to resolve it. No dev required to put together a build. This is a manual share right now if needed. I should have the script published in about a week that does this behind the scenes. If you want to do it yourself, look no further than the .git/rr-cache folder in your repository. Simple synchronization between all devs is the bare minimum that is needed. Currently this is a branch that has it’s own branch with an independent root. Wrapping the git command to intercept fetch, pull and push makes it easy to update the rerere. Any git command can be made to look at an alternate folder for the work tree and the repository itself.

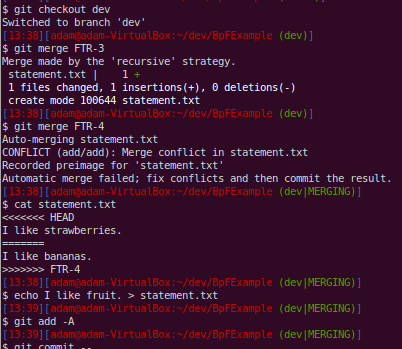

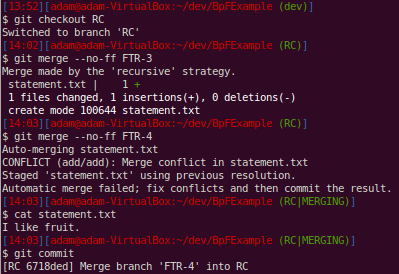

Notice that the conflict has been marked and we resolve it by just rewriting the file to make both branches agree.

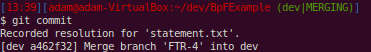

Here, since we had rerere enabled, git records how we resolved this particular conflict. This will help us when we get to the release candidate branch and other people’s work later on.

When we examine the .git folder, we can see how the resolution is stored. Just like blobs, the pre-conflict image is what determines the SHA1 hash that is the name of the directory that the conflict resolution files will be stored under. The content of these files shows just how simple even advanced concepts such as rerere are when we look at how they are implemented.

Git now reuses our previous resolution when we had that conflict on the dev branch. It does not make this an automatic commit of the merge - just in case. We examine the file that was conflicted and are fine with it and go ahead and commit the merge.

I’ll share the script that I’m writing once it’s finished. The resolutions get shared across a “resolutions” branch in the same repository.

Taking features out is more powerful than putting them in

This might sound counter-intuitive. But at the end of an iteration, a feature that you thought was done may not work as the last bits of testing on the build as a whole make releasing a no-go. Anyone should be able to take out that feature and release anyway.

So the trick is not to take the feature out of the build. You make a build with the problem feature omitted. You can integrate that feature in the next iteration when there is time. Releasing a build should be painless.

Don’t make a build to test out of the integration branch. Make a separate branch that can be reset relentlessly and tag release candidates. Reset this branch to the start commit of your iteration and merge all the features you know work.

No conflicts. Remember rerere and the like? Anyone should be able to do this if you followed the practices here. This is “why” the hard work needs to be shared.

The key is we “threw away” all previous merges and have to redo them. But remembering our conflict resolutions, this is now a trivial matter. If in doubt, we haven’t really thrown them away, they are still there to reference or use. Git’s pick-axe functionality makes it really easy to find certain code changes if you don’t know where to look.

Here we have decided that feature 3 is no good and we want to make a build without it:

Now we can see that feature 3 is not part of this release candidate:

Shared code

You will quickly note how painful keeping shared code synchronized across the many applications that you have. This is usually handled by git submodules. If you don’t have explicit contracts between the shared libraries and your client applications, there is going to be a lot of work to ensure you have the right version deployed. Adhering to OCP (open closed principle) is the only way out of this and buys the ability to have a rolling deployment. The preferred way is to have a submodule that contains all the messages needed to communicate in the system. You can enforce that only new messages get added with server-side hooks that will not allow existing messages to be modified or deleted - only new messages are allowed to be added.

Giant refactorings

Your work is as organized as is possible. Whether you elect to do this off of a certain point in time on the integration branch, release candidate branch or you started a feature branch for it, you have a way of tracking that work and can apply it as a merge, rebase or manual patch to another point if necessary. If there are large changes, we can do that work before we start on other features after a release. There is no magic bullet for refactoring across the board. Organized work and history help this - it doesn’t hinder it.

Any hardships that you may encounter will be tempered by the fact that you are relentlessly sharing your conflict resolutions and continuously integrating. PROPER BRANCH-PER-FEATURE RELIES ON RELENTLESS CONTINUOUS INTEGRATION

Toggles are a hack

There are exceptions. You’re a giant company. You need to enable a feature for a small subset of early adopter users. This is now an explicit feature that’s important to business. That’s where we all want to be but most of us are not.

Having to make architectural changes because you can’t effectively organize your work is a process smell plain and simple. Some teams are not mature enough and this may be an OK solution temporarily.

This is Git Flow Improved

Most of this way of working started from the excellent post called “A Successful Git Branching Model”. The important addition to this process is the idea that you start all features in an iteration from a common point. This would be what you released for the last one. This drives home the granular, atomic, flexible nature that features must exhibit for us to deliver to business in the most effective way. Git flow allows commits to be done on dev branches. This workflow does not allow that.

The other key difference is no back-merge into the feature. Otherwise, you will not be able to exclude this feature later in the iteration.

It will be bad if you use old tools

Not having a snapshot based history will hurt as branching is effectively copying another branch which will be slow. Not having a base of where the branch originated will make merging difficult as you do not have a base to compare how each side of development has changed. There are many other issues with having a connected-only tool to support what you do in order to work with everyone.

We can always deploy

The release candidate builds represent production ready deployable packages. This is the most responsible way of doing Continuous Deployment. We have the latest completed and tested feature at our disposal. We don’t ship any code that does not belong to a feature that’s passed QA and all other tests. Having this option gives you the best position as an IT department. Business has the power to deploy whenever it wants to - and have the piece of mind that nothing is half-baked to the best of anyone’s knowledge.